The Hugh Cudlipp lecture: Does journalism exist?

The full text of Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger's Hugh Cudlipp lecture

Alan Rusbridger

guardian.co.uk, Monday 25 January 2010

Thank you for inviting me to give this lecture in honour of the memory of Hugh Cudlipp.

Ask any British journalist who were their editor-heroes over the last 30 or 40 years and two names keep recurring. One is Harry Evans. The other is Hugh Cudlipp.

Why were they so admired? Because they seemed to represent the best of journalistic virtues – courage, campaigning, toughness, compassion, humour, irreverence; a serious engagement with serious things; a sense of fairness; an eye for injustice; a passion for explaining; knowing how to achieve impact; a connection with readers. Even if you missed their editorships – as I did with Hugh Cudlipp – both men wrote inspiring books about journalism: about how to do it, but, more importantly, about why it mattered.

It is wonderful that Jodi Cudlipp is here tonight, though I hope she will not misunderstand me when I say a tiny part of me is quite glad Lord Cudlipp is not here in person. I believe he liked and admired the Guardian. But something tells me he did not enjoy being lectured by the Guardian.

He once wrote:

"The robust tabloids flashed the Green Light, were promptly denounced by other newspapers for their gaucherie or vulgarity or lèse majesté, and then were echoed by the very newspapers who had so severely upbraided them for their frankness."

He quoted Kingsley Martin, former editor of the New Statesman:

"The Mirror says openly only what the readers of the News Chronicle and the Guardian say behind their hands."

So I don't think Cudlipp would necessarily have enjoyed sitting through a lecture by the editor of the Guardian.

The one thing Cudlipp and Evans hardly ever wrote about was business models. For one thing, they didn't have to. They lived at an age where, if you got the editorial product right, money was usually not the burning issue. There was cover price and there was advertising and – though, of course, there were many newspaper failures along the road – there was no great mystery about where revenues came from. Secondly, they didn't see that as their job. Their job was to edit great papers: other people worked out how to pay for it.

Yet the most common question most editors are now asked is: "What's the business model?"

Of course, you know why people ask. Journalism may be facing a kind of existential threat. Whether you are a 22-year-old thinking about a career in journalism, or a 45-year-old wondering if your chosen calling will see you through to retirement, it's the question that nags away all the time. Insecurity is the condition of our journalistic age.

So it's a vital question. At the same time it's a kind of deadening question for journalists to be asking of other journalists. One – honest – answer is that no one can currently be sure about the business model for what we do. We are living at a time when – as the American academic Clay Shirky puts it – "the old models are breaking faster than the new models can be put into place".

And it's a bit deadening because journalists are, as a rule, better at thinking about journalism – including the most fundamental question of all, hinted at in my title tonight – of whether there is such a thing as journalism.

If you think about journalism, not business models, you can become rather excited about the future. If you only think about business models you can scare yourself into total paralysis.

Having said all that, I am going to begin tonight by talking about one business model – in part because it is even now coming down the slipway; in part because it so radically affects some of the most stimulating ideas of what journalism is becoming, or could become.

The business model is that one that says we must charge for all content online. It's the argument that says the age of free is over: we must now extract direct monetary return from the content we create in all digital forms.

Why I find it such an interesting proposition – one we have to ask, and which, typically, that great newspaper radical Rupert Murdoch, is forcing us to ask – is that it leads onto two further questions.

- The first is about 'open versus closed'. This is partly, but only partly, the same issue. If you universally make people pay for your content it follows that you are no longer open to the rest of the world, except at a cost. That might be the right direction in business terms, while simultaneously reducing access and influence in editorial terms. It removes you from the way people the world over now connect with each other. You cannot control distribution or create scarcity without becoming isolated from this new networked world.

- The second issue it raises is the one of 'authority' versus 'involvement'. Or, more crudely, 'Us versus Them'. Again, this is similar to the other two forks in the road, but not quite the same. Here the tension is between a world in which journalists considered themselves – and were perhaps considered by others – special figures of authority. We had the information and the access; you didn't. You trusted us filter news and information and to prioritise it – and to pass it on accurately, fairly, readably and quickly. That state of affairs is now in tension with a world in which many (but not all) readers want to have the ability to make their own judgments; express their own priorities; create their own content; articulate their own views; learn from peers as much as from traditional sources of authority. Journalists may remain one source of authority, but people may also be less interested to receive journalism in an inert context – ie which can't be responded to, challenged, or knitted in with other sources. It intersects with the pay question in an obvious way: does our journalism carry sufficient authority for people to pay – both online (where it competes in an open market of information) and print?

So I want to talk about those three forks today. They are not, I think, simply esoteric points about the choices facing one industry – newspapers. If, like Hugh Cudlipp, you believe that journalism actually matters, has some kind of moral purpose and effect, then these are decisions of great significance to society as a whole.

Which – before we think about business models – is probably a good moment to introduce the man who prompted the title of tonight's talk. Last autumn I was at a government seminar on the future of local newspapers when one of the participants suddenly interjected: "I don't believe in journalism."

This was a very direct challenge to my general worldview, not to mention my job, so I sought out the person who had made it – a very interesting man called William Perrin – a former Cabinet Office civil servant who threw it all in to run a hyperlocal websitereporting on the area of London where the Guardian now lives – King's Cross.

Perrin absolutely believes in the moral power and importance of what many of us might think of as journalism. But he isn't a journalist, he doesn't call it journalism and he is completely uninterested in the monetary value of what he does. He finds other ways to pay his mortgage. This is William Perrin:

.

William Perrin: "I set up a very simple website in 2006 … to my surprise this thing took off and has been very successful. In three or four years we have written 800 articles on King's Cross and area a mile long by half a mile wide …The website we have used to drive campaigns on the ground. We've run big campaigns against Network Rail, where we secured a million pounds for community improvements. We used the website again to take on Cemex, a multibillion-pound company … we took them on and we won. We have about four people who write for the site, on average, there's up to six, but normally there's about four of us writing. We all do it as a volunteer effort. It costs us about £11 a month in cash, which is about three of four pints of beer ... we have a very strong community of people around here who send us stuff. None of the people who work with me are journalists. I'm not a journalist by any stretch of the imagination; it's an entirely volunteer effort … Some people what I do in my community some people label journalism, it's a label I actually resist."

Depending on your point of view, you may find that vision of new ways of connecting and informing communities inspiring or terrifying. I think it is both – but it is a useful starting point to thinking about the value of journalism, in every sense of the word 'value'. And it is good to be forced to think at an even more basic level – about what journalism is and who can do it.

So, let's begin by thinking about this question of what the direct value of content is. It seems to be a subject on which no one can agree. Rupert Murdoch, who has in his time flirted with free models and who has ruthlessly cut the price of his papers to below cost in order to win audiences or drive out competition ("reach before revenue" as it wasn't called back when he slashed the price of the Times to as low as 10p) … this same Rupert Murdoch is being very vocal in asserting that the reader must pay a proper sum for content – whether in print or digitally. The New York Times announced last week that it would be reinstating a form of pay wall around its content. Casual readers will get the NYT for free. Repeat, or loyal, readers will be expected to pay.

At the other end of the spectrum we have millions of William Perrins, beavering away for free, not to mention a Russian oligarch and former KGB man, Alexander Lebedev, who is experimenting with giving away everything for free – in print and digital. He isjunking the one tried and tested revenue model of people handing over money for the printed paper. So there is no agreement among publishers, never mind the public, as to whether journalism has a direct value in any form.

Many people would like Murdoch and the New York Times to succeed – who could be against anything which could be relied on to support this thing which looks like journalism well into the future?

Now, I happen to believe that Rupert Murdoch is a brave, radical proprietor who has been a good owner of the Times and that he has often proved to be right when he has challenged conventional thinking. But many people who similarly admire him have nagging doubts about whether he's right this time. The publisher of the New York Times, Arthur Sulzberger Jr, admitted last week that his own pay wall proposals are, to some extent, "a bet". Full marks for honesty. What they're doing is a hunch.

To put it another way, it may be right for the Times of London and New York, but not for everyone. It may be right at some point for everybody in the future, but not yet. There is probably general agreement that we may all want to charge for specialist, highly-targeted, hard-to-replicate content. It's the "universal" bit that is uncertain.

Murdoch, being smart, knows better than most that a printed newspaper – a tightly-edited basket of subjects and articles – becomes a very different thing in digital form. He will know the argument that says that in future you may be able to charge for mobile, but not for desktops. That specialist information may have value, general information little or none. The arguments hardly need rehearsing tonight. We all know the Walmart-Baghdad subsidy theory – that it is retail display advertising that pays for the New York Times Iraq operation, not the readers.

On mobile, we're all at the start of an experiment that is fascinating but unknown. We had no clue what, if anything, to charge for the Guardian's iPhone app when we launched it at the end of 2009. We settled for £2.39 and sold 70,000 in the first month. It's one clue to the future, not an epiphany.

This year will see a fascinating struggle for dominance between the Kindle, the Sony reader, Plastic Logic's Que, the Skiff Reader and LG's 19-inch bendy e-journal. They may all have (if they don't already) significant revenue opportunities. Things are moving so fast that these remarks may be out of date by Wednesday, when Apple is expected to launch something between an iPhone and a Kindle.

That's mobile, where different rules may well apply. Universal charging brings different challenges. For universal charging to work, the argument goes, every news organisation would have to put all content behind a pay wall. One of the favourite Murdoch arguments against the BBC is that – so long as it exists and is "free" then that makes it harder for commercial news organisations to charge, James Murdoch describes what the BBC does as "dumping free, state-sponsored news on the market". The Murdochs would like the BBC to be drastically curtailed in order for their business model to have a better chance of success.

Now, Australians sometimes find it easier to speak bluntly to fellow Aussies than we Brits do. So I read with interest a recent speech by the head of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation – called "Media after Empire" – by their director general,Mark Scott.

The "empire" in his title was not the British Empire, but old media empires. He used his speech to rebut the notion that public broadcasting in Australia should have its wings clipped to prop old media models up. Yes, it's the same issue down under.

This is the speech you won't hear from Mark Thompson – or indeed anyone in British political or regulatory life:

"This old proprietorial model, long run by media barons, operated as a form of protection from harsh realities the business might otherwise have faced. They were still vastly profitable ... The barons worked a variation of the J Paul Getty formula for success: "Rise early, work hard, strike oil". TV, radio, newspapers were their oil … Media policy amounted to not much more than a tawdry chaos of compromises designed to appease these moguls."

"Today they seem largely out of solutions – and instead challenge reality by seeking to deny a revolution that's already taken place by attempting to use a power that no longer exists, [and] by trying to impose on the world a law that is impossible to enforce."

To Scott's way of thinking, newspaper companies are facing dreadful problems because – in his haunting phrase – "technology companies [have] continually outclassed the content companies".

"It would be wonderful to be able to present you with some blinding vibrant future for the old media organisations … For newspapers, the last great hope now seems to be something called Waiting for Rupert."

Scott's argument is it would be utterly wrong to hobble the one model that does successfully produce distinguished and serious news journalism – publicly-funded broadcasters – in order to sustain a failed business model.

A little digression about the BBC. I know it is regarded as an act of faith by some that all print journalists should be baying for BBC blood, wanting it neutered or drastically reduced. I find it difficult to join that particular chorus for three reasons.

Firstly, look across the water to America, where newspapers are in as much trouble as they are here. They have no public service broadcaster to speak of to contend with, and yet they are still in desperate trouble. So you could do an awful lot of damage to the BBC and still find you had not solved the problem of newspapers because it is actually a worldwide challenge, not a specifically British one.

Secondly, as a citizen rather than competitor, I'm afraid to admit that I really like, admire and respect the BBC – including, even, its website. Now, of course, there is plenty to criticise – the BBC can be arrogant, hard to work with, complacent, needlessly expansionist and insensitive to the plight of their colleagues in the commercial sector. We need to agree, or understand, the limits of its expansion. But the BBC is almost certainly the best news organisation in the world – the most serious, comprehensive, ethical, accurate, international, wide-ranging, fair and impartial. So I hesitate to join the sometimes deafening chorus of BBC denigration, even though I suspect the Guardian would undoubtedly thrive even better in the digital world were the BBC's website, in particular, to be curtailed.

Thirdly, there is another really excellent broadcaster with an irritatingly good news website – Sky News. I have seen nothing to suggest that there is any intention to put this website behind a pay wall. So, any British newspaper intending to charge for general content would have to contend – not only with the BBC – but with the free availability of a first rate Murdoch-owned general news service on the web. All the arguments about competition from a 'free' BBC online apply to a 'free' Sky News website.

So charging might be right for some bits of the Murdoch stable of media properties, but is it right for all bits of his empire, or for everyone else? Isn't there, in any case, more to be learned at this stage of the revolution, by different people trying different models – maybe different models within their own businesses – than all stampeding to one model?

One difference between the Murdochs and most other people is that they already have a digital business in this country – a highly successful and profitable one in Sky.

The Guardian is our digital business.

And it is a business, not a charity. The paper has always employed very talented and driven commercial people. The move from Manchester to London was a tough business decision as much as an editorial one – and how right that was. Our first decade of digital growth wasn't subsidised by the Scott Trust – it was relatively modest and covered by the profits of the paper.

And, before anyone makes the obvious point that we are trust-owned and loss-making, let me make the equally obvious point that all the Scott Trust does is to enable the Guardian to compete on the same more or less level playing field as a host of other loss-making papers, whether their own cross-subsidies come from large international media businesses, Russian oligarch billions or unrelated companies within the same ownership or group.

As 2009 ground on there was no shortage of digital sceptics who were ready to call time on the business of digital publishing – mainly on the grounds that search engine optimisation (SEO) was bringing in readers who didn't stay and who were hard to monetise.

There was something in their critiques. The indiscriminate chasing of numbers will do no good long term for any serious news organisation. And it is perfectly true that 2009 was a disappointing year for those who hoped for an unbroken pattern of growth in digital advertising.

But to dismiss the potential growth of digital right now – on the basis of the worst economic crisis since 1929 – may be a little premature.

Here's Sir Martin Sorrell, head of WPP, and one of the most influential figures in advertising anywhere in the world. He employs 140,000 people in 106 countries and takes $60bn a year in billings, with revenues of $14bn. He makes weather in advertising, the same way as Murdoch does in print.

.

"I would hope that within five years, so let's say 2013, or something like that, we would be at least one third in digital. We know that customers are spending 20% of time online. So if clients are spending 12% and consumers are spending 20% – and I've seen some evidence to suggest they are spending more than 20% – then there's a natural gravitational pull to 20% of the budgets being spent online … my guess is that when we get to a third of our business in 2014 we may very well want to up that percentage to 40% or even 50%."

Sorrell is not saying all this advertising is going to newspapers, and he has some sympathy for the pro-pay wall arguments. But he is signalling a steadfast belief that the digital share of the advertising cake is going to grow very sharply and significantly.

My commercial colleagues at the Guardian – the ones who do think about business models – are very focused on that, want to grow a large audience for our content and for advertisers, and can't presently see the benefits of choking off growth in return for the relatively modest sums we think we would get from universal charging for digital content. Last year we earned £25m from digital advertising – not enough to sustain the legacy print business, but not trivial. My commercial colleagues believe we would earn a fraction of that from any known pay wall model.

They've done lots of modelling around at least six different pay wall proposals and they are currently unpersuaded. They're looked at the argument that free digital content cannibalises print – and they look at the ABC charts showing that our market share of paid-for print sales is growing, not shrinking, despite pushing aggressively ahead on digital. They don't rule anything out. But they don't think it's right for us now.

So, having said I wouldn't talk about business models, I've said far too much. But that's because it's difficult to ignore this particular business model in talking about how the future of journalism is shaping up.

As an editor, I worry about how a universal pay wall would change the way we do our journalism. We have taken 10 or more years to learn how to tell stories in different media – ie not simply text and still pictures. Some stories are told most effectively by a combination of print and web. That's how we now plan our journalism. As my colleague Emily Bell is fond of saying we want it to be linked in with the web – be "of the web", not simply be on the web.

Some stories can be told in one sentence plus a link. Some journalists are fascinated by the potential of the running, linked blog. Andrew Sparrow's minute by minute blog of Alastair Campbell's appearance before the Chilcott inquiry was a dazzling example of this new form of reporting, which relies on the ability to link out to sources and other media, including original documents and even (in the lunch break) Campbell's own Twitter feed.

You can see journalists everywhere beginning to get all this.

Ruth Gledhill at the Times is, for me, an inspired example of how you can layer reporting – with the most specialist material in the blog (linked to yet more specialist source material on the web – and the most general material in newsprint.) The paper will carry a paragraph on a controversial sermon by the Bishop of Chichester. Gledhill will explain its significance on her blog, and link to the full sermon for those who want the source. Readers can then debate the text on the blog and follow other links. It's called through-editing.

Ben Brogan does something similar at the Telegraph, as he did in pioneering form at the Mail previously. Robert Peston and Nick Robinson increasingly regard their blogs as the spine of what they do at the BBC. That's where they put the detail: the Ten O'Clock News is the icing.

This, journalistically, is immensely challenging and rich. Journalists have never before been able to tell stories so effectively, bouncing off each other, linking to each other (as the most generous and open-minded do), linking out, citing sources, allowing response – harnessing the best qualities of text, print, data, sound and visual media. If ever there was a route to building audience, trust and relevance, it is by embracing all the capabilities of this new world, not walling yourself away from them.

Two further points about this fluid, constantly-iterative world of linked reporting and response: first, many readers like this ability to follow conversations, compare multiple sources and links. Secondly, the result is journalistically better – a collaborative-as-well-as-competitive approach which is usually likely to get to the truth of things, faster.

When I think about universal pay walls, I wonder how this emerging world of editing and writing would change. How would you handle a story like the Guardian's exclusive revelation that Google was about to drop censorship in China – a hugely significant story that bounced around the world within seconds of us breaking it online at 11pm on January 12?

Had there been a universal pay wall around the Guardian that would have been a difficult story to handle.

- Wait and publish in print? But we knew that Google was about to post the story on its own blog at 6pm Eastern.

- Publish digitally and hope that people would buy a day pass to read it? But in the time it took to key in your credit card the essence of the story would have been Twittered into global ubiquity. It is one of the clichés of the new world that most scoops have a life expectancy of about three minutes. A valuable three minutes for the FT or the Wall Street Journal if it's market sensitive information. Most people, with most information, and without subscriptions paid for by their companies, are happy to wait.

If you erect a universal pay wall around your content then it follows you are turning away from a world of openly shared content. Again, there may be sound business reasons for doing this, but editorially it is about the most fundamental statement anyone could make about how newspapers see themselves in relation to the newly-shaped world.

The internet has, of course, has had a dramatic impact on the economics of newspapers. But it has changed almost everything else as well. The whole world is in the middle of a revolution. This may sound an old-fashioned thing to say, because it has been true for at least 10 years. Things are still changing overwhelmingly and fast; in part, because the first digital generation is still growing up.

There's been one change so big and obvious in the last decade that we may not have noticed it: the new media have disappeared. They are just media now: the means through which our world must be experienced. No one under 25 can remember a world without them. Everything shows up on screens, from the big ones we sit in front of all day at work to the small ones on the phones with which we spend our leisure hours – when they're not sending us emails.

These screens give us very much more than written words, and they change the ways we understand the world – from text to multimedia; from linear to hypermedia; from passively absorbing material to learning how to navigate actively – and we change them right back.

Don Tapscott, in his book Growing Up Digital, has explored some of the ways in which the technologies of the last 20 years have helped develop a generation of fierce independence; of emotional and intellectual openness; of inclusion; biased towards free expression and strong views; interested in innovation, used to immediacy; sensitive to/ suspicious of corporate interest; preoccupied with issues of authentication and trust – which includes having access to sources; interested in personalisation or customisation rather than one-size fits all; not dazzled by technology, but more concerned with functionality.

In the digital world, the distance between impulse and action is shorter than ever before. The goal of most interface design is to make it vanish altogether. In this open and immediate world millions of people are realising they can be publishers, that they don't need intermediaries. The British Museum or the Tate or the Royal Society or Imperial College don't have to wait any longer for the BBC or Channel 4 to ring and suggest a programme or series; they can make their own. The same is true of any writer, scientist, politician, photographer or activist. To call this the "democratisation of communication", or of information, or of culture seems somehow inadequate.

Governments are freeing up their data, records and information; museums and galleries are throwing open their doors; NGOs and charities are becoming publishers; universities are opening their lecture halls; scientists and corporations are sharing knowledge in ways which would have been unimaginable even 10 years ago. And then there is Google, with its ambition to digitise and organise all human knowledge since time began.

Mention Google, and we think of China: the spread of disorganised information is balanced by organised disinformation and censorship. We can't know yet who will win, but we know what side we must be fighting on.

We know that the fastest – almost vertical – growth in amongst all this is what is rather lumberingly called 'social media'. This involves the power to generate content and connect with others at low, or no cost; in real time. The innovation that made all this possible – crudely, developments associated with Web 2.0 – is now happening alongside the evolution of so-called semantic web, which wants to find better ways of understanding the meaning of content and how to find it, organise it and share it.

Where do news organisations think they fit into all this? Are we in, out – or in only if we can make it pay in the immediate future?

I try to imagine the Guardian deciding it doesn't want openly to be part of this world I've just described and I struggle. And do, please, forgive me for talking about the Guardian a bit, but it is necessarily the thing I am most focused on, and which illustrates the point that one size may not fit all.

The other day I interviewed the playwright Michael Frayn for the Guardian and Observer archive. He described life on the Manchester Guardian he joined in 1957 – just over 50 years ago, but within one working lifetime.

The paper he joined was still a provincial morning paper, hugely influential, but not always readily available on the day outside the north-west and parts of London, Oxford and Cambridge.

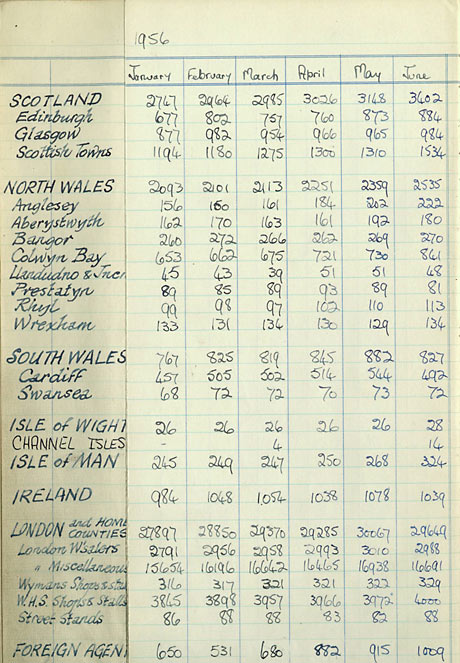

This ledger shows the sale of the Manchester Guardian in and around Manchester in January 1956 – the year before Frayn joined the paper.

The Guardian's Manchester sales in 1956

The Guardian's Manchester sales in 1956It was a paper which counted every sale in Rusholme, Didsbury or Cheetham Hill.

Today, in print, the Guardian is, even now, the ninth or 10th biggest paper in Britain.

On the web it is, by most measurements, the second best-read English-language newspaper in the world. If the New York Times really does start charging for access, the Guardian may become the newspaper with the largest web English-speaking readership in the world.

In December the journalism we're producing at GNM was read by 37 million people around the world – very roughly a third in the UK, a third in North America and a third in the rest of the world.

Go back to the 1956 Manchester Guardian ledger of sales outside Manchester, the paper Frayn joined.

The Guardian's sales outside Manchester in 1956

The Guardian's sales outside Manchester in 1956The last line shows the worldwide sales of the Guardian – "foreign agents" – to be 650 copies. We had more readers in Colwyn Bay than in the rest of the world.

This clever little widget is effectively our digital circulation map today. It shows you in real time a sample of the people reading the Guardian from just one of its 32 servers.

In Michael Frayn's professional working life the Guardian has grown from sending 650 copies abroad to becoming one of the eight most read newspapers in the world, a ranking that includes two Chinese, one Japanese and one South Korean.

I think back to an essay CP Scott – for 57 years editor of the Guardian – wrote in 1921 – not the famous essay on the separation of comment and fact – but the preface to the American edition of the centenary history of the Manchester Guardian.

"The world is shrinking. Space is every day being bridged. Already we can telegraph through the air or the ether, from Penzance to Melbourne and tomorrow we shall be able to talk by the same mechanism. Physical boundaries are disappearing … What a change for the world! What a chance for the newspaper!"

Scott would, I think, have been intensely intrigued to know that the paper he edited for so long and in whose name a family trust was established to continue the spirit of the Guardian – was so openly available and read around the world. That it was becoming as influential in Beijing and Washington as in Paris or Delhi. That its reporting could change the minds of governments, inspire thinking, defy censorship, give a voice to the powerless and previously voice-less. The same is true of all the British newspapers who have grasped the importance of the web.

It's certainly a powerful thought for journalists on all these papers. Reporters and commentators who were digital sceptics even a couple of years ago now realise they are part of, and linked to, a worldwide conversation. An art critic will be picked up and referenced in Berlin; a defence correspondent in Moscow; an environment writer in Copenhagen. Tell them their work was about to disappear from that conversation without the production of a credit card, and they would not be overjoyed unless they knew it was the only answer in business terms.

In an industry in which we get used to every trend line pointing to the floor, the growth of newspapers' digital audience should be a beacon of hope. During the last three months of 2009 the Guardian was being read by 40% more people than during the same period in 2008. That's right, a mainstream media company – you know, the ones that should admit the game's up because they are so irrelevant and don't know what they are doing in this new media landscape – has grown its audience by 40% in a year. More Americans are now reading the Guardian than read the Los Angeles Times. This readership has found us, rather than the other way round. Our total marketing spend in America in the past 10 years has been $34,000.

Nor is all this being bought by tricks or by setting chain-gangs of reporters early in the morning to re-write stories about Lady GaGa or Katie Price. In that same period last year, our biggest growth areas were environment (up 137%), technology (up 125%) and art and design (up 84%). Science was up 81%; politics 39% and Comment is Free 38%.

This is the opposite of newspaper decline-ism, the doctrine which compels us to keep telling the world the editorial proposition and tradition we represent are in desperate trouble. When I think of the Guardian's journey and its path of growth and reach and influence my instincts at the moment – at this stage of the revolution – are to celebrate this trend and seek to accelerate it rather than cut it off. The more we can spread the Guardian, embed it in the way the world talks to each other, the better.

And that leads to the third fork – the one that pitches authority against involvement, or Us against Them.

Have a look at this website, recently launched, which aims to do for books what Facebook has done for general social engagement.

Bookarmy is a rather clever site – completely free – where, once you've registered, you can share your passion for books with thousands of others. You can join forums around types of books, or individual books. You can have virtual discussions with authors, link your reading group to others, publish your own reviews and so on. Apart from the authors themselves, there are no "authority" figures here.

Compare it with, say the Times books pages. Here the reverse is true: the emphasis is on "expert" reviews by critics, with not much interest in what you might have to say about a particular book. There is a kind of book group, but you would have to say that interactivity is not the feature it most promotes.

Why am I comparing these two sites? Because both are owned by Rupert Murdoch.

BookArmy – though it avoids saying so – is an offshoot of Harper Collins. The two enterprises point in completely different directions. As it was explained to me, the point of BookArmy is to get as many avid book readers engaged as possible and learn as much as possible about their likes and dislikes. At some point in the future (the theory goes) publishers will no longer need to spend a fortune on marketing Max Hastings' next book by lavishing money on Waterstones or in print. They will go to BookArmy and say "We know you have a database of the 80,000 people in the country who read books of military history. We'll give you our targeted marketing spend instead."

BookArmy is a telling illustration of two aspects of the digital world.

- One is the ability of digital disrupters (in this case, even within the same company) to take one bit of a newspaper and do it with a conviction, range, depth and passion that a portmanteau print-based newspaper cannot match, especially in digital form. It is the unbundling of newspapers.

- And the second is the only hope of matching the power of the these digital disrupters is to harness the same energy and technologies which they are using.

So, all credit to the Murdoch empire: they are themselves beavering away to unbundle parts of the print world in digital. How should other papers which care about books react? Sit behind a pay wall while the audience is unbundled for us by the make-it-free bit of the Murdoch empire? Or get out there and have a chance of being part of the way the rest of the world is going?

If you still want convincing look at this site, the Artsdesk, on which a lot of arts writers who used to work for the national press have set up their own culture site. That's right, they want to unbundle the arts coverage from newspapers. I imagine they begin each day with a prayer session for all national newspapers to follow Rupert Murdoch behind a pay wall. That's their business model.

We know about the audience for social media forms of engagement – 350 million active users on Facebook, 2.5bn pictures posted a month; Twitter growing at 400% a year. We know people spend much more time with such sites than with newspaper websites.

Now, of course, lots of journalists find this hard to take. We are supposed to be the ones in the know, or with special access or insights. "Social media is interesting," say the digital sceptics, "but it may be transient – and it has got nothing to do with what we do. Our brands are about authority."

But this position – that journalists are uniquely knowledgeable and insightful – is a hard one to sustain to anyone who looks at the blogosphere with an open mind, or looks at the astonishing way in which a tool like Twitter can be customised into a personalised news feed to give you extraordinarily rich and deep content on specialised subjects faster (and in many cases deeper) than any newspaper could hope to match.

Does all this mean you sack Michael Billington, with his 39 years of experience, and ask all the Guardian readers in the National Theatre audience to tweet their reviews in 140 characters or less?

No – but you could keep both.

Many of the Guardian's most interesting experiments at the moment lie in this area of combining what we know, or believe, or think, or have found out, with the experience, range, opinions, expertise and passions of the people who read us, or visit us or want to participate rather than passively receive.

There have been long-standing innovations such as Travel – where the experiences of readers, properly harnessed, is necessarily going to be broader, deeper and more eclectic than any us-to-them travel section based solely on the individual experiences of travel writers. 433 views of Amsterdam, rather than one.

There has been over-by-over cricket – not replacing Mike Selvey or Vic Marks, both of whom played for England and know a thing or two, but adding the enthusiasm, passion and graveyard humour of cricket-loving Guardian readers to the blogging of Rob Smyth or Andy Bull.

There is Comment is Free – infinitely more diverse, wide-ranging and, at its best, enlightening than any newspaper ever achieved by simply pushing the opinions of a few columnists out of the door and slamming it shut.

The last year has seen us crowd-source tax-avoidance – the internal Barclays documents that can (after a legal fight) be found on Wikileaks and whose publication undoubtedly led to changes in legislation and attitudes to corporate tax avoidance. It began with a traditional piece of investigation by David Leigh, followed by participation and analysis by people who really understood this world. It was classically an example of "our readers know more than we do" – the bit of new media theory which seemed so daring when first aired by Dan Gillmor in 2004.

There have been other examples of crowd-sourcing:

- The G20 protests – another example where old fashioned reporting was allied with the mass observation of people we wouldn't call reporters, but who were, on the day, able to do acts of journalism. The truth about the death of Ian Tomlinson probably wouldn't have been uncovered without the doggedness of one reporter – Paul Lewis – but it certainly wouldn't have emerged without thousands of people searching their own digital record of the day for the crucial evidence.

- There was the widget we built to allow 23,000 Guardian readers to help us sort through hundreds of thousands of documents relating to MPs expenses. The Telegraph's original investigation was brilliantly executed. But the future will also be about asking for help in digesting vast and complex amounts of data.

- There was the exercise of asking readers to get to the bottom of Tony Blair's tax affairs– expertise which did not lie within our own offices and which could have cost many thousands of pounds to buy in.

There has been Twitter and the way individual journalists have used it to draw on the expertise of specialist followings. Significant communities building around reporters or subjects – 1.5 million and counting who have chosen to follow the Guardian's technology team. The most enterprising reporters are learning how to use Twitter to research; as a customised, specialised, personalised wire service; to break news; to market and distribute content; to build communities and bring them into the Guardian.

There was the Guardian's environmental site – something we went into knowing we couldn't possibly do such a huge and complex subject on our own. So we joined up with a network of environment sites and bloggers. We link to them; they link to us. We give them a platform and deliver a large audience (and a share of advertising). They give us a diversity and range we could not hope to achieve ourselves. It's difficult, in our industry, to argue with 137% growth.

And there was Trafigura. Again, this started as a piece of conventional reporting by David Leigh (not forgetting the BBC, and colleagues in Norway and the Netherlands). They uncovered a truly shocking story about a company which had hitherto been comfortably anonymous and which wanted to keep it that way.

After dumping toxic waste in the Ivory Coast Trafigura was hit with a class action by 30,000 Africans who claimed to have been injured as a result. The company employedCarter-Ruck to chivvy journalists into obedient silence and then, having secured the mother of all super-injunctions, made the mistake of warning journalists that they could not even report mentions of Trafigura in parliament.

One tweet and that legal edifice crumbled.

This animated map of what the Twitterati were discussing, or searching for, showed how – within 12 hours of my tweeting a suitably gnomic post saying we had been gagged – Trafigura became the most popular subject on Twitter in Europe.

Some tweeters beavered away trying to find out what it was they were banned from knowing. One erudite tweeter uncovered something called the 1840 Parliamentary Papers Act, which no media lawyers seem to know about. Others pointed to where a suppressed document was available. Others found and published the parliamentary question we were warned not to report.

Within hours Trafigura had thrown in the towel on the injunction and dropped any pretence that they could enforce a ban on parliamentary reporting. The mass collaboration of strangers had achieved something it would have taken huge amounts of time and money to achieve through conventional journalism or law.

These examples show how – so long as it is open to the rest of the web – a mainstream news organisation can harness something of the web's power. It is not about replacing the skills and knowledge of journalists with (that ugly phrase) user generated content. It is about experimenting with the balance of what we know, what we can do, with what they know, what they can do.

We are edging away from the binary sterility of the debate between mainstream media and new forms which were supposed to replace us. We feel as if we are edging towards a new world in which we bring important things to the table – editing; reporting; areas of expertise; access; a title, or brand, that people trust; ethical professional standards and an extremely large community of readers. The members of that community could not hope to aspire to anything like that audience or reach on their own; they bring us a rich diversity, specialist expertise and on the ground reporting that we couldn't possibly hope to achieve without including them in what we do.

There is a mutualised interest here. We are reaching towards the idea of a mutualised news organisation.

To end where we began: Hugh Cudlipp does not feel to me like an editor who would have wanted to cut himself off from a revolution such as we're living through. He feels like someone who would have seized on today's technological opportunities to embrace the Mirror readership – just as he did with the Mirror's Live Letters. He lived by the credo – when in doubt, ask the readers.

One of his favourite Mirror front pages came at the height of the controversy over whether Princess Margaret should be allowed to marry Group Captain Peter Townsend, who, as well as being a Battle of Britain hero, was also a divorced man. One Monday in July 1953 the Mirror put the question to its readers, with a voting form on the front page which, in pre-Twitter days, readers had to cut out, stick in an envelope, attach a stamp and post.

By Friday 70,000 Mirror readers had responded, with a 97% vote in favour of Margaret being allowed marrying Townsend.

The sequel – nine days later – was a rap over the knuckles by the Press Council – "strongly deprecating as contrary to the best traditions of British journalism the holding by the Daily Mirror of a public poll in the matter of Princess Margaret and Group Captain Townsend." The following day the Mirror led on Lord Beaverbrook denouncing this "smug, pompous resolution" and itself describing the censure as "ridiculous".

So newspapers criticising self-regulators isn't new either.

Yes, there are lots of concerns about this world I'm describing, not least the ignorant, relentlessly negative, sometimes hate-filled tone of some of what you get back when you open the doors. That can sometimes feel not very much like a community at all, let alone a community of reasonably like-minded, progressive intelligent people coming together around some virtual idea of the Guardian. So there are a throng of issues around identity, moderation, ranking, recommendation and aggregation which we – along with everyone else – are grappling with.

But let's grapple with them rather than dismiss them or turn our backs on them. Let's not leave the field so that the digital un-bundlers can come in, dismantle and loot what we have built up, including our audiences and readers. "Comment is Free" ... "Publish and be Damned" … Fleet Street is the birth place of the tradition of a free press that spread around the world.

There is an irreversible trend in society today which rather wonderfully continues what we as an industry started – here, in newspapers, in the UK. It's not a "digital trend" – that's just shorthand. It's a trend about how people are expressing themselves, about how societies will choose to organise themselves, about a new democracy of ideas and information, about changing notions of authority, about the releasing of individual creativity, about an ability to hear previously unheard voices; about respecting, including and harnessing the views of others. About resisting the people who want to close down free speech.

As Scott said 90 years ago: "What a chance for the newspaper!" If we turn our back on all this and at the same time conclude that there is nothing to learn from it because what 'they' do is different – 'we are journalists, they aren't: we do journalism; they don't' – then, never mind business models, we will be sleep walking into oblivion.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Med

No comments:

Post a Comment